Alignment is (Still) a Great Idea; Misalignment is (Often) a Reality

- Erwan Hernot

- Dec 4, 2024

- 4 min read

While alignment—defined as the coherent execution of strategy—is often discussed as a logical extension of strategy itself, it remains largely theoretical. In reality, the risks of misalignment in organizations are very real. This paper aims to analyze the causes and consequences of misalignment, offering a framework for understanding and addressing it. Readers may recognize familiar misalignments within their own organizations.

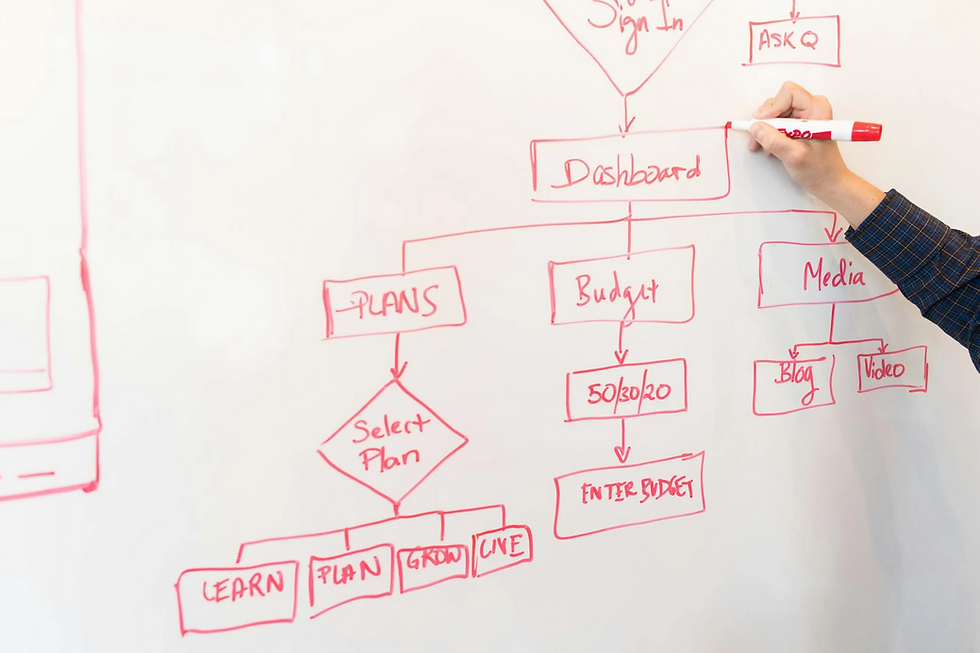

Let’s begin with some definitions, using the diagram above. Horizontal alignment (red arrows) coordinates the major components of an organization, from its mission to its management systems (1). Strategy answers the question, "How?" It encompasses the arrangement of actions and resources. Operational capability includes the structure and tools. Structure defines roles, responsibilities, relationships between functions, decision-making processes, and collaboration mechanisms. Tools refer primarily to IT and production systems. Resources symbolize financial flows and human capital. Lastly, the management system encompasses incentives, defining compensation and recognition based on objectives and performance evaluation. Human resources management plays a parallel role, maintaining and developing the capacity of team members through recruitment, management, and skill enhancement.

When members of an organization are aligned, there is a clear, shared understanding of the mission, vision, and overarching goals. Employees at all levels connect their contributions to the organization's objectives, giving greater meaning to their work. Alignment fosters collaboration and cooperation between teams and departments. When everyone works towards common goals, information, resources, and expertise are more willingly shared, improving teamwork and synergy. Aligned organizations streamline decision-making processes, enabling faster responses to market changes, emerging trends, and customer needs. Such organizations are also more agile and adaptable to external changes.

The responsibility for achieving alignment lies primarily with top management, tasked with defining the vision, mission, and strategic objectives and ensuring they are 1) understood and 2) acted upon across the organization. Middle managers, such as department heads, translate these visions and strategic objectives into concrete action plans for their teams, aligning departmental activities and resources with these goals.

However, several challenges disrupt this theory: At the strategy level, there are two major risks of misalignment, which can often compound each other.

First, when an organization changes strategic direction, it may settle for incomplete alignment. Examples include entering new markets, adopting new technologies, or undergoing mergers and acquisitions. Such shifts require consolidating certain functions, harmonizing processes, restructuring teams, creating new departments, or redefining existing roles. However, leaders often fail to reassess the entire organizational system.

Second, the strategy itself may lack clarity or stakeholder agreement. Objectives and priorities may be unclear or inconsistent, leading to confusion and a lack of direction. Without clear criteria for decision-making, decisions may appear arbitrary and illegitimate. In such cases, individuals retreat into their functional silos. For instance, a function may implement changes to improve its efficiency while complicating workflows for the rest of the organization, reinforcing perceptions of overall disorganization.

Other issues include misaligned organizational structures, outdated processes, and incompatible tools. For example, adopting a new digital platform may necessitate changes in employee skills, workflows, or hierarchical structures. Without these updates, productivity losses, frequent errors, and delivery delays become inevitable. Communication, coordination, and accountability problems multiply, creating confusion about responsibilities and difficulties mobilizing resources. Siloed workflows hinder collaboration, innovation, and the sharing of best practices. Skills critical to achieving strategic objectives remain underdeveloped.

Misaligned management leads to contradictory approaches among managers. Even when a CEO concludes a meeting by asking, “Are we aligned?” and everyone nods, subsequent actions often fail to reflect the agreed direction. Leaders may recite the vision, organizational strategy, and key metrics at will, but how well do middle managers two or three levels below truly understand and align with these goals? When middle managers fail to grasp or communicate their departments’ contributions to overall objectives, coherent action becomes nearly impossible. Misaligned metrics within incentive mechanisms exacerbate the problem, resulting in wasted effort, poor results, frustration, and high turnover.

Faced with this array of issues, one might ask: Why do some organizations tolerate misalignment?

The answer often lies in the complexity and delicacy of the realignment process. Realignment begins in the minds of individuals—are they convinced of the need for change? If not, resistance is inevitable. The first step is securing the recognition and buy-in of the leadership team, which requires co-creating the strategy with its members. The next steps involve cascading objectives down the hierarchy using tools like OKRs and KPIs, a process that takes time and effort. Leaders must spend more time with managers to ensure they fully understand and embrace their roles.

However, challenges persist. Senior management often views strategy development as its exclusive domain, leaving implementation to others. Leaders may underestimate the importance of helping others understand, adopt, and align with strategic priorities. Efforts to secure consensus are minimal or treated as an afterthought, undermining alignment. Middle managers, poorly equipped with top-down communication packages, may fail to translate strategic goals into actionable plans or opt for inaction due to perceived risks.

Moreover, organizations often neglect upward communication, which allows for feedback and horizontal alignment. In large, complex organizations, information flow and access to leadership levels are often obstructed. Without upward communication, leadership misses critical insights from middle managers, who focus on localized results at the expense of broader goals.

Returning to our CEO and their closing question: Rather than assuming alignment with a general inquiry, they would benefit from explicitly validating each leader’s understanding and commitment to the objectives. Asking how leaders plan to collaborate across silos to achieve alignment further fosters cooperation. Such efforts emphasize that alignment is an ongoing process, requiring continuous reinforcement and recalibration.

*(1) Various models depict organizational components differently, including J. Galbraith's Five Stars, McKinsey’s 7S framework, and the work of Jonathan Trevor and Barry Varcoe in the Harvard Business Review.

Comments