Despite Complexity, Decision-making Process Stays The Same

- Erwan Hernot

- Dec 4, 2024

- 5 min read

In the current discourse, one often hears: 'Managerial innovations driven by the digital age and the pandemic are paths that must be followed.' At the core of these innovations lies decision-making, which is the focus of this paper. Setting the stage: businesses no longer operate in a simple environment where experience alone suffices for decision-making: 'This problem resembles one we solved last year. Let’s address it the same way.' Have they fully grasped this shift? Not quite, as they remain structured to handle a complicated environment (where analysis deduces causes and effects) without recognizing that it has, in fact, become complex (where analysis does not deduce causes and effects). Like management methods and organizational structures, the decision-making process has yet to evolve. Here’s why and what could be done about it.

Everything must change so that nothing changes…

Maintaining 'traditional' (or rational) decision-making processes upholds Command & Control management. It involves escalating decisions to someone higher up, rather than delegating them to those who can decide with relevant knowledge. This translates into a proliferation of committees and decision-making layers that need to be climbed. The higher one is in the hierarchy, the more they are consulted, spending increasing time in meetings. 'Compared to twenty years ago, processes have lengthened considerably: a process that used to take three days now takes eight on average,' reports Yves Morieux (1). This escalation is implicitly justified by the strong hypothetico-deductive reasoning capacity attributed to executives. From this perspective, managers are seen as capable of applying the rules of formal logic to any decision, accounting for all dimensions and elements of the problem.

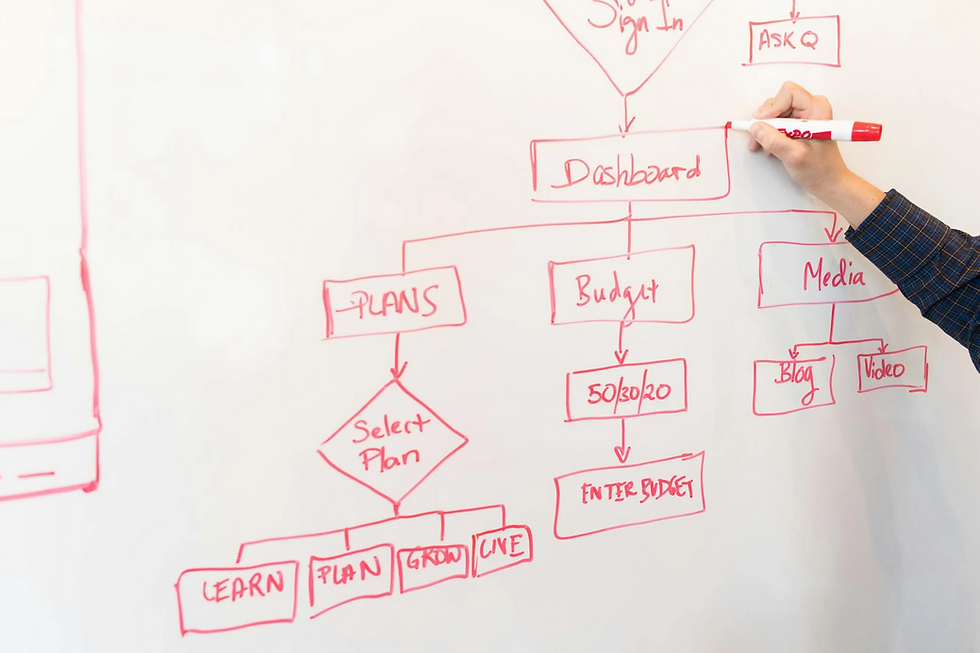

The rational decision-making process unfolds as follows: analyzing the situation, formulating the problem (building it based on a hypothesis), identifying all possible alternatives, associating each decision with a set of consequences, ranking potential consequences according to a preference criterion, identifying the decision that provides maximum efficiency within constraints, acting, and validating the initial hypothesis. While this model is logically sound, it is not always suited to a complex environment. The first limitation lies in the relationship between the volume of information and decision-making performance, which can follow an inverted U-curve. Information helps up to a point; beyond that, overload diminishes performance. To avoid challenging Command & Control management, there is often a temptation to boost managerial performance through artificial intelligence (AI).

Indeed, coupling AI with big data automates an increasing number of human decisions across industries. AI excels at analysis, with algorithms often outperforming human judgment in recurring decisions and recommendations. Many companies have invested millions in IT systems to centralize data for decision-making by executives. More centralized data is believed to enable better decisions. This perpetuates Taylorist principles: there are those who think and those who execute. However, doing more of the same does not lead to different solutions. Producing quality decisions in a complex environment requires a Copernican revolution, which has been slow to start:

The manager cannot rely on probabilities to predict outcomes. There is no guidebook to quickly validate their chosen approach. Decision consequences are often only known after the fact, sometimes ambiguously. In a complex environment, even objectives can be unclear or conflicting. Data does not neatly align to construct problems; instead, problems are shaped from puzzling and uncertain materials, which the manager must interpret. For example, you sell a product that has been a star in its category for years. You fear disruption from a startup but have no evidence to prove it or idea what form such competition might take.

Analysis is not always effective. Many issues elude the rational decision-making model due to excessive uncertainty or the human mind's inability to process everything. In military strategy, Carl von Clausewitz, cited by Christian Morel (2), described this uncertainty with concepts of fog and friction. Managers must acknowledge this and abandon the belief that they can conquer complex, unpredictable realities. They must make decisions while accepting them. International perspectives on French managers provide insight (3): intellectual jousting over the perfect solution continues to dominate meetings, often at the expense of a more modest 'experiment/test/learn' approach.

'Managers spend only 30% of their time adding value (4); the rest is devoted to reporting on dozens of performance indicators. Companies have multiplied these indicators sixfold.' Despite managers’ strong cognitive abilities and AI support, this structure is outdated. Knowledge must be extracted from data—something AI struggles with—to make informed decisions. Furthermore, information overload stifles creativity. Notifications continuously demand attention, preventing the brain from entering its 'default mode.' Yet this inactivity is when managers synthesize recent learning, connect divergent information, and generate creative, unexpected solutions to complex problems.

The 'silo' structure does not facilitate cross-departmental cooperation. Few decisions can be made by a single individual with all the necessary information. Cooperation is psychologically taxing, as it challenges established ways of thinking and requires compromises. Decisions are often distributed among departments, each operating within its own logic, which is reflected in decision-making processes and the data used. For instance, marketing might add new features to a product without considering the training needed for sales administration. This decoupling produces suboptimal solutions but avoids confrontations between silos and differing logics. Political games further delay direct and open discussions. Decisions are instead routed implicitly to specific departments. Consequently, decision-making processes are difficult to grasp. Meetings often end with no clear decisions, and responsibilities are diluted.

Emotions and Decisions

For over 60 years, leading thinkers (e.g., H. Simon on bounded rationality, D. Kahneman on Systems I and II, and more recently neuroscience) have revealed the flaws in purely rational decision-making models, highlighting cognitive biases that affect even top executives. Decision-making involves two circuits: rational processing and emotional memory. The latter is immediate, often unconscious, and produces knowledge influencing decisions. It has historically ensured survival (e.g., fear-triggered responses like a racing heart). This circuit evaluates decisions in terms of emotions and sentiments. Consequently, decisions can sometimes be less relevant, rooted in emotions or memories unrelated to the situation's true stakes.

This dual emotional/rational pathway is evident among international managers in French CAC 40 companies (6). Meetings often feature rigorous rational debates, but decisions are revisited informally at the proverbial watercooler, where discussions are much more emotional.

The issue isn’t ignorance of optimal decision-making processes but a desire to retain power where it currently resides. If this resistance could be overcome, how might decision-making adapt to complexity?

A Framework for Complex Decision-Making

Managers must restructure their thinking. Rational decision-making is not inherently flawed; rather, the irrational belief in its universality must be challenged. Managers and leaders should officially embrace the second circuit (emotions), practicing emotional intelligence to understand their own reactions to problems and decisions. Failure to decode one’s emotions leaves managers at their mercy. Recognizing their feelings frees managers to think differently:

They can complement linear rational thought (A to B to C) with nonlinear processing, pursuing multiple threads of thought in parallel. Emotional motivation integrates diverse information, resolves puzzles, and finds innovative approaches to complex problems.

They confidently practice critical thinking, making reasoning transparent and fostering faster exchanges between stakeholders. This reduces rhetoric, abstract ideas, and decontextualized judgments that lead to disputes. Surprisingly, critical thinking enhances rationality by depersonalizing differences of opinion.

They involve teams inclusively in decision-making processes. 'If it’s about us, don’t do it without us.' Inclusion facilitates execution, and managers build a toolkit of decision-making methods (consent, consensus, ad hoc, autocratic) tailored to situations.

They delegate decisions and responsibility closer to the field, provided employees have the skills, information, and resources needed. However, delegation isn’t a cure-all and doesn’t resolve information overload. Subsidiarity requires processes to support it.

They simplify decision-making processes to enhance organizational agility. Shorter decision loops engage reflective capacities, fostering accountability and alignment with company goals.

At the end of this paper, one might criticize most companies. I refrain from judging, as decision-making touches on power, a fundamental aspect of human psychology. Consider "I Was in a Hurry" by Christian Streiff, a former PSA CEO who, after a stroke, struggled with the loss of the rational cognitive capacity that had defined his strength. Or imagine a leader discussing their emotions about a budget. Changing decision-making processes reshapes how leaders see themselves—a transformation that will take years.

Comments