"Strategy? Employees don't get it"

- Erwan Hernot

- Jan 1, 2025

- 7 min read

This remark from an executive is far from an exception. Yet, very often, the strategy in question is well documented. The issue is neither insignificant nor neglected: a limited understanding of the strategy by managers and teams leads to an execution that falls short. Some management experts (1) estimate that only a fifth of the company's workforce actually understands the strategy to be implemented. Only one in five people grasps its ins and outs. It is unlikely to be executed and to produce the expected results. The question that then arises is: "What strategy are the other four people executing?" The answer can be summed up in a few words: each department tends to operate according to its own logic. The problem is not just one of execution. Consequently, it goes beyond the dissemination of the strategy and includes its design. This is what this paper details.

Before even addressing what it proposes, the first axis of understanding to address is the strategy itself: what is it? Strategy requires observing the connections between the company, its market, its competitors, and its partnership networks. Performance is perceived globally. This is the level that primarily interests shareholders and executives. Their motivations are economic, technological, and organizational. The business strategies of competitors are analyzed, along with regulatory compliance and the constraints of the results to be produced. We seek to understand how the organization generates performance, innovation, and value creation: strategy indeed organizes actions and resources. It outlines roles, responsibilities, and relationships between functions, decision-making processes, and collaboration mechanisms. It relies on operational capacity, which encompasses structure and equipment, primarily including information and production systems, as well as the management system. The latter includes incentives that set remuneration and recognition of efforts by following objectives and evaluating performance. This definition may be a bit long, but it has the merit of raising awareness about the articulation of these different elements in the strategy. A poor understanding of the whole leads to a misalignment of these elements (see here)… even before considering poor execution by each department.

Observe what happens when strategy is discussed in a company. A formal meeting brings together the “knowers” (usually the executives) in front of managers and their teams. Downward communication makes up 80% of the time, and the remaining 20% is reserved for questions that no one (in France) asks! Result: to fill time, the knowers paraphrase what they’ve just said, without likely achieving greater engagement from their audience. Everything is codified: the knowers display assertive behavior (they are confident) and emphasize their reasoning more than their commitment. The audience is used to the exercise: they wait for it to be over and prepare to debrief the meeting in the hallway. No one takes ownership of the subject. Several problems limit the effectiveness of this exercise and complicate the understanding of the strategy.

First, executives stick to a single level of discourse, even if it is also intended to reach the staff. No matter how good the thinking behind the strategy, it is a waste of time if it is not in the heads but also the hearts and hands of the people who must execute it. In other words: emotion is a powerful ally of a purely intellectual presentation. “Nothing great in the world has been accomplished without passion.” (2) Yet, strategy is still developed at a level where the human element has no place. The hitch is that it is precisely at this (human) level, among the teams, that it is carried out… or not. Strategy answers the question “Where are we going?” The general objectives are the practical translation of it. They answer the question: “How are we going to get there?” To be understood, the strategy should be more closely aligned with vision and mission. Vision refers to the desired future state of the company. It answers the question: “What do we want to become?” It involves setting a course while considering the common aspirations of stakeholders (which, in itself, is already a major task) as well as the context. If known and shared, the vision can engage and motivate all internal stakeholders in the company: “Inspire me!” The mission is the reason for the company's, team's, or employee's existence. It answers the question: “What are we doing? Why do we exist?” It relies on the ability to improve one’s job, activity, or added value. This is an important element of self-motivation. Vision and mission are what connect the formulation and the implementation of strategy. They build the emotional commitment that often makes the difference for team productivity and results. The quality of this link is a condition for performance. If it is lacking, it leads to a loss of meaning. This is what employees are more or less explicitly demanding, especially since the confinements.

However, in strategy communication, executives assume that words carry meaning. Their assumption is that each time they say a word, the image it evokes for them will appear identically in the minds of their audience. To be convinced, one only needs to have been the key player of an (anxious) executive team on the eve of a strategic communication. How every word becomes a stake, the subject of all attention. It’s a mistake: meaning is triggered in the minds of their interlocutors. Words are just triggers of meaning. Each of us has our own meaning because we filter them through our frames of reference, which come from our experiences and backgrounds – by definition, very different. Similarly, information is not communication, and vice versa. Information is raw material used in the communication process to create a result that shares meaning and understanding. Information does not carry meaning for someone until it has gone through this process. Simply disseminating strategy is no substitute for discussing its content. Communication is a far more complicated process than disseminating information because it seeks to create both cognitive and emotional effects.

Many executives do not consider that times and constraints have changed. In the past, we knew, and we could deduce what we didn’t know. In a way, there was a limited range of good answers to the problems and constraints of the environment. Access to understanding was easier. An analysis (based on expertise) allowed us to establish correlative, causal, and logical relationships. Then we applied the appropriate operational practices. This is the traditional version of strategy as a linear sequential process. It is still often used. Executives clearly separate its formulation from its execution afterward. Obviously, they formulate it at the start of a process when they know the least about the subject and the events that are likely to occur. Yet, they cannot bring themselves to accept the uncertainty of this beginning, even though they can rarely identify all the factors that will shape the future. But everything must be done so that employees believe in the unwavering relevance of the strategy and, consequently, in the competence of the executives (until the strategy changes, usually along with the executives, without much explanation). The problem with this approach is that it prevents managers from playing their role as strategic co-creators, which they de facto have in a complex world. Executing a strategy indeed generates, along the way, new information such as the responses of competitors, regulators, and customers, which transform the initial situation, the subject of the strategy. It is difficult in this case not to incorporate this new information into the previously drawn plan. Yet, this is what happens very often. At worst, a linear process strategy tends to produce more of the same, even if it’s not working, to “stay the course.”

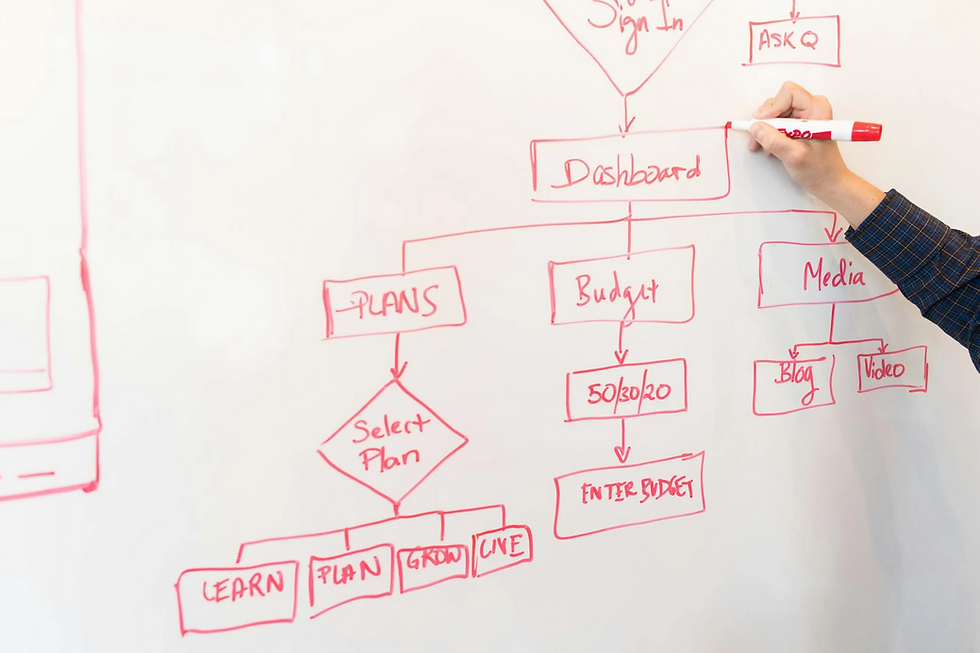

The alternative (3) is to think of strategy not as a linear process but as an iterative loop that facilitates progressive and comprehensive understanding. Today, strategists face situations where cause and effect can only be deduced retrospectively, and there isn’t initially a set of good answers. Markets, ecosystems, and corporate cultures, like all complex systems, are insensitive to a reductionist approach where everything is organized like a machine, because the actions themselves change the situation unpredictably. This loop involves the following approach: making sense of a situation, identifying or even producing and applying relevant knowledge, making choices about what to do and what not to do, executing/making things happen, revising based on new data that is linked to what we already know (in response to what has been done). These different steps can take place in a more formal process that includes strategic planning, the budgeting phase, the resource allocation phase, and performance management. Lessons, or even models, can emerge if executives conduct experiments with their managers, without fear of failure. And these discussions should not only be concentrated at the top of the hierarchical pyramid. They must spread to all levels of the company. Once the strategy is clear, it is possible to adopt a few simple rules that apply to all situations as it is communicated down to teams and frontline managers. These rules prevent endless discussions in search of perfect agreement among stakeholders. The illusion of consensus is abandoned, but local managers are empowered with room for maneuver.

Strategy used to be developed from ideas originating from executives, imposed on stakeholders, and on which they had no influence: “It comes from the top, and we obey.” In the complex world, strategy is not “external” to stakeholders. If the framework is provided by executives, it is then co-constructed, meaning it results from the decisions and actions of managers, while at the same time shaping them. This comes at the price of a shared reference system that each member of the company understands and agrees to integrate into their own reality to become an active participant.

(1) Communicating Strategy, Phil Jones, 2008

(2) Introduction à la philosophie de l’Histoire, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1820 - 1830

(3) Closing the gap between strategy and execution, Donald N. Sull, MIT Sloan Management Review, summer 2007, vol. 48

Photo : Leeloo Thefirst

Comments